Our arrival in Vienna, or Wien as it’s written in German, was uneventful. The station felt larger and glossier than Prague and, later, Budapest, and overall it was less a grand, imposing vault like those stations, and more of a burrowed mall, like New York’s current Penn Station. We quickly found our way around and took a subway out to our hotel, which was near the Riesenrad, a landmark Ferris wheel.

Before we got to that though, the trick was to find the luggage lockers. In our trip research, we learned that Wien Hbf had overnight luggage lockers, but it wasn’t clear how long they could be used. What’s posted is overnight, 24-hour only, but we found numerous accounts of them being used for multiple days at a time. Ultimately, an Austrian Railways worker confirmed what we’d read in an online forum: You pay for a night upfront, but if you come back later than that, you simply pay for each successive period retroactively. They don’t clear out abandoned lockers for at least a week.

That would do just fine for our purposes; we’d only be in Vienna for two days. David locked up the skis and sorted all his ski equipment into a single large bag, and that gear lived at the station while we traveled light.

We bought 2-day transit passes, and made sure we understood the ticket-validation process. We took a subway ride of about fifteen minutes, and in short order arrived at the Hotel Kunsthof, a delightful, airy hotel not far from the station, that provides fresh apples every day at the front desk. We settled in and got some rest; Vienna had a lot to offer.

Day 1

Vienna was the capital of the Habsburg-era Holy Roman Empire, later the Austro-Hungarian “dual monarchy”. It was a city of wealth and power for centuries, and the old part of the city still bears the look of Enlightenment-era imperial monarchy, as opposed to the more medieval bearing of Prague. The various sights are all well-organized, and in the tourist district, it was hard not to feel like we were in a kind of theme park.

Our first activity was the Spanish Riding School, so-called because four hundred years earlier, Emperor Charles VI had the school built to train young noblemen in the art of combat horsemanship. Since then it’s evolved into an art form of its own, and the horses are trained to take various poses based on those early martial moves. It’s called Spanish because the horses were originally from Spain; the Lippizan breed, and sometimes they are referred to as Lippizaners.

We saw the horses perform in their Morgenarbeit, or morning workout, standing room only in a large oval viewing area overlooking the training pitch. Later, we took a tour of the facility, and got to see backstage. We were not permitted to take photos of the horses, however.

We took some time for some smaller museums of interest. There was the globe museum, which features large globes, tiny globes, celestial globes as well as terrestrial globes, as well as a couple of extraterrestrial globes. There was a globe in Hebrew as well.

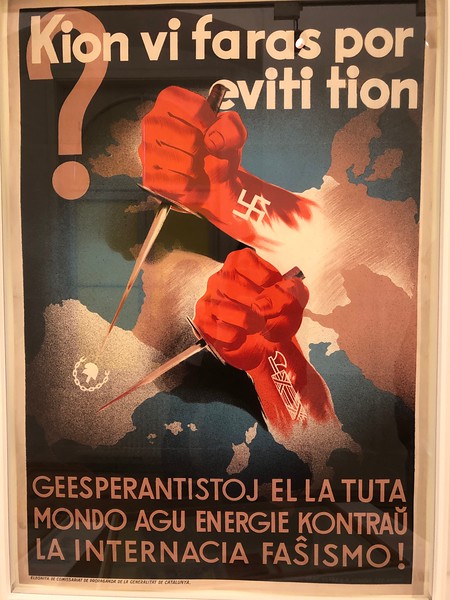

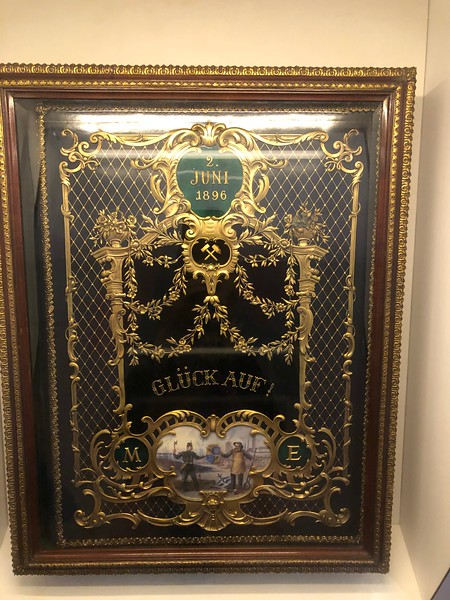

A stone’s throw away was a small museum devoted to Esperanto, the artificial language meant to unite all humanity. While it was easy to make jokes about it, the fact that fascist Germany and Italy cracked down hard on Esperanto, as did Stalinist Soviet Union, made Esperanto seem more like a lofty goal than a William Shatner punchline.

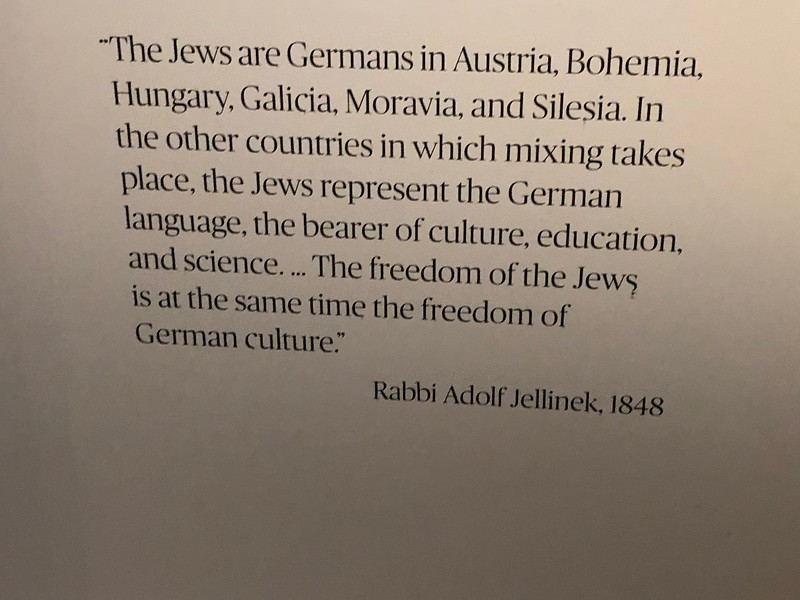

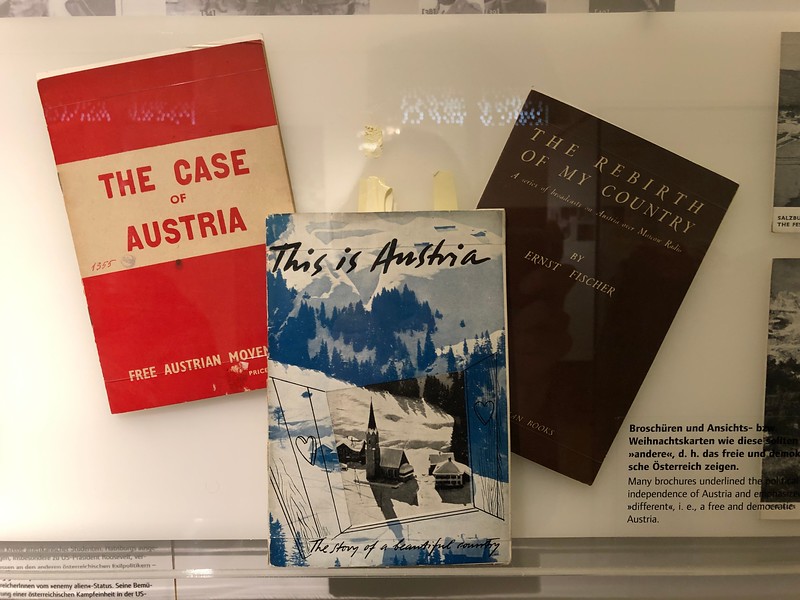

We also visited the monument to the struggle against war and fascism, and the Jewish museum. While we visited sites and learned about the history of Judaism in every city we visited, Austria’s was especially notable.

From the treatment of the Jews by various monarchs over time, to being the birth nation of Adolf Hitler, followed by the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, to post-war politics that still displayed open anti-Semitism, Austria has much to say about the history of anti-Semitism, as well as how easily a democracy can slide into fascism.

It didn’t end after the war; in the decades since, Austria’s political system has still had to confront these ugly aspects of human nature.

Somewhere, sometime, we managed to squeeze in the Haus Der Musik. This was an interactive museum about sound, and music. Unfortunately, many of the interactive exhibits weren’t working or weren’t working well, so we ended up passing through some well-lit exhibits that we read about.

Two interactice exhibits that were working well involved motion. In one, you would stand in a circle while kaleidoscopic images were projected onto a wall. Extend your arm one way, and the volume would increase; extend another, and the loop of music being played would change in rhythm and texture. That one, I really liked.

In the second, last before the gift shop, you’re invited to virtually conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. After picking a classic tune, you step on a stage and grab a conducting wand. A video of the Philharmonic plays along with the music, and your conducting controls the speed and volume.

I have to say, I liked this one quit a bit, but it seemed to lag against my movements, alternately speeding up and slowing down. Eventually, the video stopped and cut to a closeup of the First Chair violinist, who told me, in German with subtitles, that the Blue Danube frequently brought him to tears, but my conducting accomplished that for all the wrong reasons.

Day 2

On our second day in Vienna, we took a more personal detour to visit the neighborhood David’s grandfather lived in before immigrating to the US. We got the street address from an uncle, one of granddad’s brothers, and looked it up online. On the way, we stopped at the train station to buy tickets and check on our luggage; everything was in order.

The neighborhood was a refreshing change from the tourist district. While David and I both appreciate history, we also like seeing how regular people live – the unvarnished truth of a place. That is what we found.

First of all, the neighborhood felt very working middle class, predominantly filled with ethnic and religious minorities. While the specifics were different, we suspect the dynamic was similar in the time his grandfather lived there, just a few years after the First World War and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire.. David’s grandfather was Jewish and the family ran a small shop in the neighborhood. Such a neighborhood in the last years of the Habsburgs is now home to what were mostly Muslim families and shops today.

We stopped at a cheese booth and had a good conversation with the clerk. David’s a bit of a gourmand when it comes to fromage and we wanted something to make sandwiches later, and wanted something specific to the place. We must have been taking too much time though, because eventually the owner came over, presumably curious why the sale was taking so long, but we had a good conversation with him.

The owner was from Afghanistan. He had been in Austria several years, and spoke both German and English. He still had family back home. While the quality of life was better than in his home country, his community still faced discrimination from the local police, and throughout the country there was considerable prejudice against them from native Austrians. He seemed disappointed when I told him it was much the same in the United States.

Knowing the history, having seen what we’d seen, and then talking to this man to hear his story, the throughline from past to present was clear. People will go to great lengths to seek a better life for themselves. People can also feel very threatened by those who are different, whether by custom, religion, or skin color. As David put it, much of the history that we visited was essentially of people being rotten to one another. We know better, and we ought to do better.

That said, we took the train back to the hotel neighborhood, and checked the box on a sight we’d been looking forward to for the whole trip: the Riesenrad.

The Riesenrad is a large ferris wheel, notably used for a scene in Orson Welles’ movie The Third Man. It’s a thriller set in post-war Vienna, pitting a journalist investigating his friend’s mysterious death against an opportunistic American black marketeer, played by Welles himself. In the scene, Welles’ character muses to the hero on how individual, faceless, lives don’t matter in the long run of history.

In a sign of how we must be getting old, and the movie even older, no one we asked among the hotel staff or the ticket sellers knew anything about the movie or its connection to the Riesenrad – even though Orson Welles’ likeness is painted onto the signs.

Afterwards, we shared an ice cream and returned to the station, boarding our next and final train ride to Budapest – a city neither of us had ever been to, and which represented the Cold War more than anything else.